How Do Chillers Work?

The Cool Science Behind Commercial Cooling Systems

Think of chillers as the unsung heroes of modern comfort—those massive, humming machines tucked away in mechanical rooms and rooftops, working tirelessly to keep your office bearable during a New York summer. While your home air conditioner gets all the glory, chillers are the heavy-lifters of the cooling world, quietly maintaining the perfect climate in skyscrapers, hospitals, and data centers across the city. But how exactly do these industrial-grade cooling systems work their magic?

The Chiller Working Principle: A Sophisticated Cooling Dance

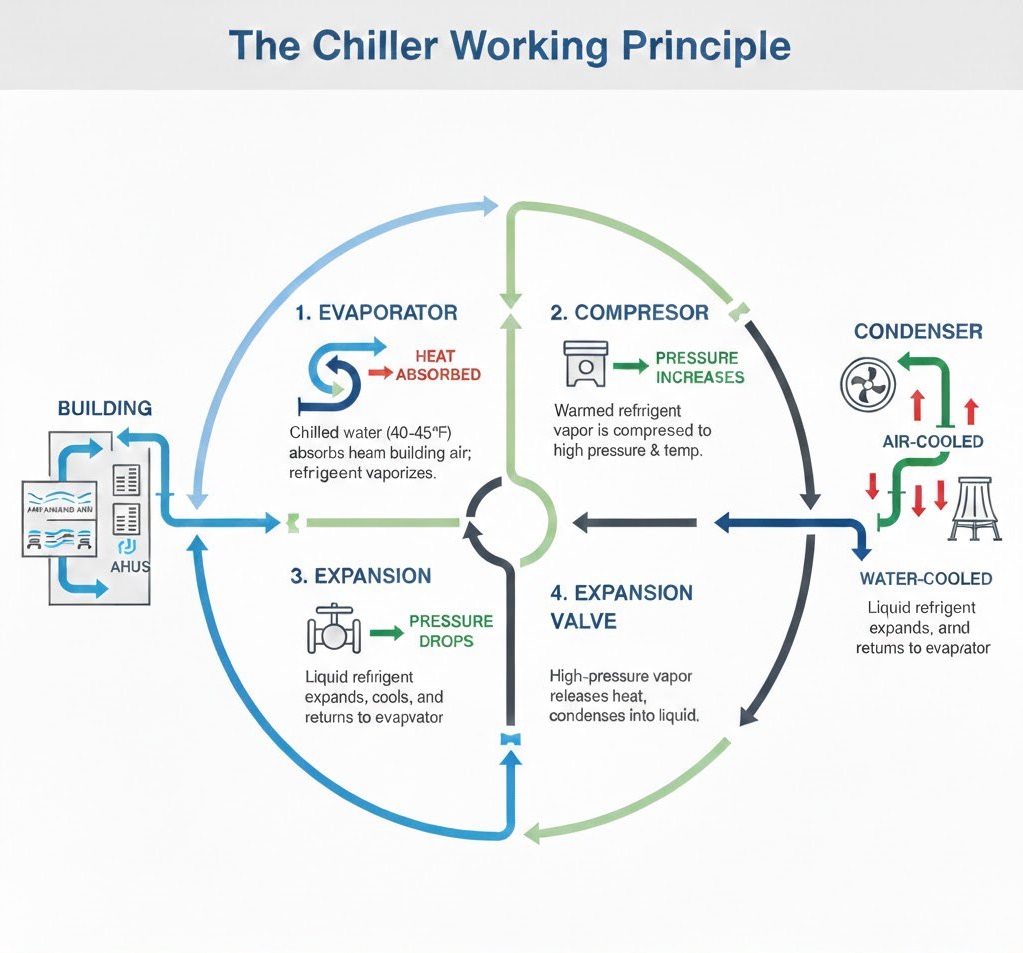

At its core, a chiller operates on the same fundamental principle as your refrigerator—it’s just exponentially more powerful. The refrigeration cycle involves four key components working in harmony: the evaporator, compressor, condenser, and expansion valve. Here’s where it gets interesting.

The process begins when the chiller’s refrigerant absorbs heat from water circulating through the evaporator. This chilled water—typically cooled to around 40-45°F—then flows through a building’s pipes to air handling units (AHUs) and fan coil units, where it absorbs heat from indoor air. Think of it as a continuous loop of thermal exchange, moving heat from where you don’t want it to where it doesn’t matter.

Meanwhile, the refrigerant, now warmed and vaporized, moves to the compressor where pressure increases dramatically. This high-pressure, high-temperature vapor then enters the condenser, where it releases all that absorbed heat to either air (in air-cooled chillers) or water (in water-cooled systems). Finally, the expansion valve reduces pressure, and the cycle begins anew—hundreds of times per hour.

How Do Water-Cooled Chillers Work?

Water-cooled chillers are the preferred choice for large commercial buildings in NYC, and for good reason. These systems use cooling towers to dissipate heat, making them significantly more efficient than their air-cooled cousins—typically 10-15% more efficient in warm climates.

Here’s the sophisticated part: the condenser water loop connects to a cooling tower, where warm water cascades over fill material while fans pull air upward. Evaporation removes heat from the water (the same reason you feel cold when wet), and the cooled water returns to the chiller’s condenser. It’s an elegant solution that leverages physics rather than brute force.

Chiller System in Building: The Big Picture

Understanding how chillers integrate with building systems reveals their true complexity. The chilled water produced doesn’t magically cool your office—it requires a sophisticated distribution network. Here’s what’s happening behind those walls:

The Primary Loop:

- Chiller produces cold water (40-45°F)

- Primary pumps circulate water through the chiller

- Water flows to secondary distribution system

The Secondary Loop:

- Variable speed pumps distribute chilled water to floors

- AHUs and fan coil units use the cold water to cool air

- Return water (now warmed to 55-60°F) flows back to the chiller

This two-loop system allows buildings to respond efficiently to varying cooling demands—brilliant engineering that saves thousands in energy costs annually.

Air-Cooled vs. Water-Cooled: A New York Perspective

| Chiller Type | Efficiency (EER) | Installation Cost | Best Application | Approximate Price Range |

| Carrier 30RB Air-Cooled | 10.5-12.5 | Lower | Buildings without cooling tower access | $25,000-$75,000 |

| Trane CVHF Water-Cooled | 13.0-16.0 | Higher | Large facilities with space for cooling tower | $50,000-$150,000 |

| Daikin Magnitude Air-Cooled | 11.2-13.8 | Lower | Rooftop installations | $30,000-$90,000 |

| York YVAA Water-Cooled | 14.0-17.5 | Higher | High-efficiency applications | $60,000-$175,000 |

Air-cooled chillers offer simplicity—no cooling tower, no condenser water treatment, less maintenance. They’re perfect for smaller buildings or rooftop installations where space is premium. However, they work harder in summer heat, consuming more electricity when you need cooling most.

Water-cooled systems demand more infrastructure but deliver superior efficiency year-round. For Manhattan skyscrapers, this efficiency translates to hundreds of thousands in annual savings, making the higher upfront investment worthwhile.

What is the Difference Between HVAC and Chiller?

Here’s a question that confuses many: aren’t chillers part of HVAC? Yes and no. HVAC (Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning) describes the entire climate control system, while a chiller is specifically the component producing cold water for cooling. Think of it this way: HVAC is the orchestra , and the chiller is the lead instrument.

A typical HVAC system in smaller buildings might use rooftop units or split systems that directly cool air. Chillers, conversely, cool water that’s then distributed—a crucial distinction for large commercial applications where centralized cooling offers better control and efficiency.

Do Chillers Run in Winter?

Surprisingly, yes—even during New York’s frigid winters. Many buildings maintain year-round cooling needs in interior zones, server rooms, and data centers. Modern facilities often employ free cooling or “waterside economizers” in winter, using cold outdoor air to cool condenser water without running the compressor. It’s like getting free cooling courtesy of Mother Nature.

What is the Main Problem with Chillers?

The Achilles heel of any chiller system? Efficiency degradation over time. Tube fouling in heat exchangers, refrigerant leaks, and compressor wear gradually reduce performance. A well-maintained chiller should deliver 15-20 years of reliable service, but neglect can slash efficiency by 20-30% within just a few years.

Regular maintenance—including tube cleaning, refrigerant analysis, and oil changes—isn’t optional; it’s essential. Smart building managers in NYC invest in preventive maintenance contracts, understanding that a $5,000 annual service prevents $50,000 emergency repairs.

Are Chillers Better Than AC?

For large buildings, absolutely. Individual AC units simply can’t match the efficiency, control, and capacity of a properly designed chiller system. However, “better” depends on application. Your 1,200-square-foot Brooklyn apartment doesn’t need a chiller—that would be using a sledgehammer to crack a walnut.

Chillers excel when:

- Cooling loads exceed 20 tons

- Multiple zones require different temperatures

- Year-round reliability is non-negotiable

- Long-term energy costs outweigh upfront investment

The Future is Smart and Efficient

Today’s chillers bear little resemblance to their ancestors. Variable speed drives, magnetic bearing compressors, and sophisticated building automation systems have transformed these machines into precision instruments. The latest models from manufacturers like Trane, Carrier, and Daikin achieve efficiency levels unimaginable a decade ago, with some water-cooled systems approaching 20 EER.

The integration with smart building systems means your chiller can now anticipate cooling needs based on weather forecasts, occupancy schedules, and utility rates—automatically optimizing performance while minimizing costs. It’s not just cooling; it’s intelligent climate management.

The Bottom Line

Understanding how chillers work reveals the sophisticated engineering behind everyday comfort. These systems represent a triumph of thermodynamics, mechanical engineering, and automation—working invisibly to maintain the climate-controlled environments modern life demands.

Whether you’re a facility manager optimizing building performance or simply curious about the infrastructure making New York livable, appreciating chiller technology offers a glimpse into the complex systems supporting urban life. The next time you walk into a perfectly cooled lobby on a sweltering August day, you’ll know exactly what’s happening in that mechanical room upstairs.

Ready to dive deeper into building systems and HVAC technology? Explore our related guides on cooling tower maintenance, energy efficiency strategies, and smart building automation.